Conclusions from the showcase at World Water Week 2019 Stockholm, Sweden.

Written by Aina Virginia Bituin Eriksson

The effects of climate change are increasingly felt around the globe through changes in weather patterns and the intensification of weather related disasters. Such changes pose challenges to the security of communities and nation states, and may worsen situations in conflict prone areas. Water’s centrality to healthy ecosystems and human wellbeing makes it a key element in building stable societies.

At World Water Week 2019, Stockholm Climate Security Hub brought together four speakers to demonstrate how climate driven hazards pose risks to human security. The messages from four different countries were similar: climate security is multidimensional and dependent on vital aspects of local resilience. Furthermore, reducing climate insecurity necessitates the cooperation within the international community.

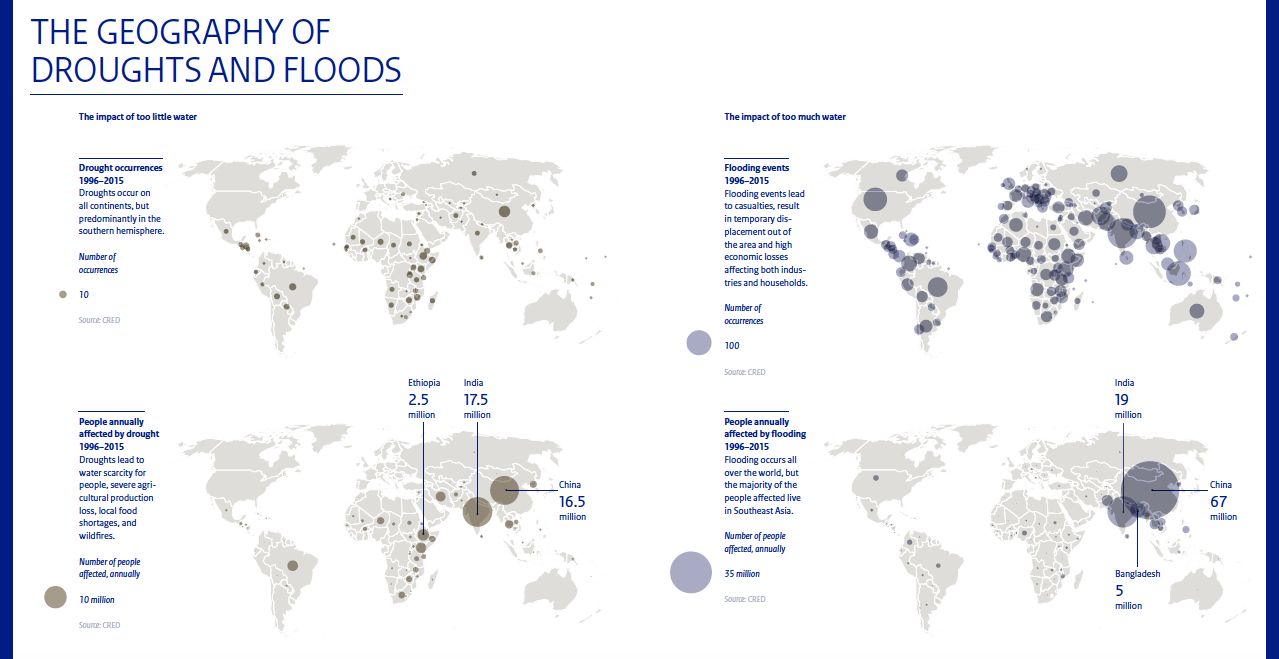

Climate change is increasing the frequency of floods and droughts, which undermine resilience.

In South Sudan climate-related security risks are heightened by changes in seasonal rains. South Sudan’s main water source is rainfall supplied throughout the country by the many rivers, including the three largest, the Sobat, the White Nile and the Bhar al-Ghazal. Alier Oka, Undersecretary at the Ministry of Water Resources and Irrigation of South Sudan explained that, although blessed with abundant rainfall, the lack of storage, inadequate sanitation and insufficient government funding make it a challenge to supply South Sudan’s population with clean water. Water management is complicated further by increased variability in rainfall. As a result flashfloods, landslides and drought bring a series of health issues and economic setbacks that in themselves undermine resilience.

Due to these challenges, water in South Sudan is unevenly distributed, aggravating ongoing conflicts between pastoralists and farmers. The search for water forces communities to move, leads to competition for and confrontation over resources, and can result in inter-community conflicts.

Weak governance, inadequate infrastructure and fragile institutions make some countries especially vulnerable to water- and climate-related security risks.

The Geography of Future Water Challenges study shows that the areas most burdened by water-related disasters are located in Africa and Asia. Referring to the study, Dr. Elizabeth van Duin, Director for Water, Soil and Marine Affairs, Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management, Netherlands, stressed that climate-related security risks are often complex and situation specific. Yet most cases require both immediate action and long-term planning with an adaptive approach. However, investing in long-term planning is often less attractive to the international development community. Building resilience in conflict prone areas therefore faces a double dilemma: conflict and insecurity means a lack of capacity to address and reduce climate driven risks, at the same time as insecurity makes communities more vulnerable to the effects of climate change.

In areas where long-term strategies to cope with climate change already exist ongoing conflict poses a substantial risk to successful adaptation strategies.

Muna Luqman, founder of Food4Humanity Yemen, and Dr Shaddad Al-Attili, Former Head and Minister of the Palestinian Water Authority, spoke passionately about examples of the weaponization of water in international conflicts. Water infrastructure, trade routes and roads are often targeted, more for political effect than military advantage, at the expense of the civilian population. Luqman explained that the destruction of pumping stations had caused many villages in Yemen to go without water, affecting thousands of livelihoods, disrupting school attendance for young women and causing serious health problems. In Palestine water reservoirs had been destroyed undermining any actions towards adaptation in the face of climate change. Perhaps worst of all are the long lasting effects of targeting water in warfare, such as the spread of disease through inadequate sanitation – as UNICEF notes in the 2019 report Water Under Fire, children under the age of 5 are nearly 20 times more likely to die from diarrhoeal disease than from violence in conflict.

Pro-active, rather than reactive, political leadership is needed to build resilience to climate-related security risks.

The lack of political will remains a hurdle in addressing climate-related security challenges in conflict areas. Inger Buxton, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Sweden, suggested raising awareness through specific examples of the impact of climate change on security. But she noted that awareness-raising couldn’t be an end in itself.

“The international community must address these risks through existing institutional arrangements, such as in development and climate adaptation plans, in NDCs and through climate and development finance that supports the resilience needed to deal with the potentially destabilizing effects of climate change. These tools and institutions need to start including the issue of climate-related security risks in their normal practices.”

Dr Shaddad Al-Attili pointed out that upholding international humanitarian law is essential in mitigating climate-driven insecurity. “Forgetting the essence of our 1.5 degree commitment, and not holding those who hinder this target accountable, that is what will cause damage.”

“The effects of climate change and the multidimensional nature of climate security reach beyond geographical and political borders,” said Johan Schaar, from the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute, in his concluding remarks. “This means that the international community needs to and address climate security as a multi-faceted problem, simultaneously affected by increased natural disasters, lack of effective governance or infrastructure and lack of pro-active leadership.”